The Pileated Woodpecker -- © Dave Spier

It’s our largest woodpecker and almost as long as a crow. A white patch on top of each black wing and white underwing linings make it a flashy flier. The body and tail are also black. If you can see the red crest, you know it’s a Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus, which translates to "crested tree-cleaver"). Closer inspection of this shy species, usually requiring binoculars, will reveal a white stripe extending from the top beak almost to the back of the head and then down the neck to the shoulder. The throat is white and there is a small white line over the eye. Adult males have a red forehead and red streak between the cheek and throat. On females the red is confined to the main part of the crest at the back of the crown.

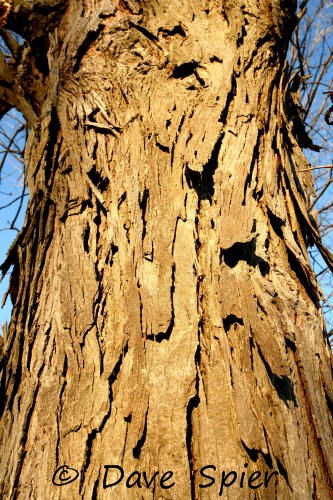

Pileateds, nicknamed "log-cocks" and "cocks-of-the-woods," live mainly in mature forests, but are sometimes seen in suburbs, parks and even villages. They are year-round residents but may shift territory depending on food supplies. Their preferred diet is carpenter ants and the birds will excavate long, rectangular holes to extract them from trees. Pileated Woodpeckers locate their prey by listening for the insect’s chewing sounds. The woodpeckers also eat other insects, larvae, berries, and nuts in the wild. I’ve seen photos of these birds at suet feeders, but my feeders are too close to the house and almost never attract a wary pileatus. Other local woodpeckers (Downy, Hairy, Red-bellied, sapsucker and flicker) are regulars to semi-regulars.

Besides eating wood-damaging insects, pileateds contribute to their woodland ecosystem by chiseling a new nest cavity every spring. The previous year’s nest then becomes available for other residents such as flying squirrels and screech owls.

The range of the Pileated covers the eastern half of the United States, portions of the Pacific Northwest and most of southern Canada. By density, though, it is most numerous in the old conifer and deciduous forests of the southern states.

The population of Pileated Woodpeckers declined sharply in the 1800’s as forests were converted to farmland and the remaining birds were shot for target practice. Conservation laws and the reversion of fields to second-growth woodlots has allowed the number of woodpeckers to rebound, but it is not what anyone would consider numerous.

Corrections, comments and questions are always welcome at northeastnaturalist@yahoo.com or connect through my Facebook page and photo page. There's also a community-type page for The Northeast Naturalist. Other nature and geology topics can be found on the parallel blogs Adirondack Naturalist and Heading Out.