Grassland Bird Surveys at Ganondagan SHS south of Victor, NY (southeast of Rochester) will expand in 2017. Two primary goals of the surveys are to support the designation of Ganondagan as a NYS Bird Conservation Area (BCA) in 2017 and to aid in assessing conservation and habitat-restoration efforts going forward. Help will be needed and greatly appreciated. Data will be collected using eBird, a free program. ("About eBird" and data-entry instructions for both the free website and free Mobile App are linked at the bottom.*) While grassland birds are emphasized, it's important to record ALL the bird species detected along with their counts or estimated counts. For conservation purposes, we need to know population trends.

For general information on NYS BCA's, go to http://www.dec.ny.gov/animals/30935.html This is a state-level program on state lands, but otherwise it's similar to Audubon's Important Bird Areas (IBA) initiative.

The first 9 survey points (out of 61 planned) are active and can be used by any ebirder. Go to Hotspot Explorer - http://ebird.org/ebird/hotspots - and type in "Ganondagan SHS" and you'll see a list of all the locations. The two general hotspots are always available for any sort of birding at Ganondagan or for birds detected between survey points.

The protocol for the Ganondagan SHS grassland bird surveys, along with maps and sample data sheets, has been revised and can be emailed as a 4-page PDF. Stationary point counts will be 5-7 minutes long depending on habitat. Essentially it's five minutes in open habitat and seven in the more wooded settings. A series or sequence of two or more of the 5-7 minute counts at one point would aid detectability studies for each species reported.

|

| eBird Hotsops (red markers) at Ganondagan SHS (satellite view) |

|

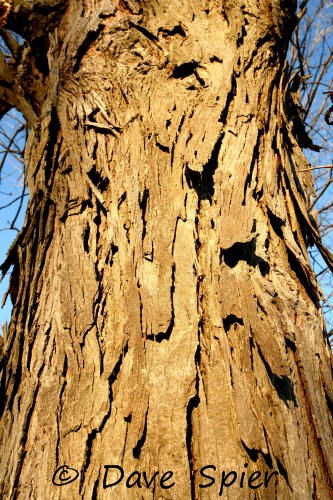

| Eastern Meadowlark, a grassland nesting species (© Dave Spier) |

List of eBird hotspots at Ganondagan SHS with links and GPS coordinates:

Ganondagan SHS http://ebird.org/ebird/hotspot/L522250 42.9635518, -77.4154615

Ganondagan SHS--Fort Hill site http://ebird.org/ebird/hotspot/L697829 42.9615576, -77.4322844

survey pt. (Bluestem Unit, 4.7) http://ebird.org/ebird/hotspot/L3656677 42.964159, -77.426105

survey pt. (Bluestem Unit, 4.8) http://ebird.org/ebird/hotspot/L3601763 42.961625, -77.427503

survey pt. (Bobolink Unit, 8.13) http://ebird.org/ebird/hotspot/L4709300 42.95462, -77.42846

survey pt. (Dogwood Unit, 3.6) http://ebird.org/ebird/hotspot/L4723726 42.96454, -77.42163

survey pt. (Farmhouse, 7.12) http://ebird.org/ebird/hotspot/L4723719 42.95934, -77.42494

survey pt. (Fort Hill, 5.10) http://ebird.org/ebird/hotspot/L4721388 42.96411, -77.43416

survey pt. (Fort Hill, 5.9) http://ebird.org/ebird/hotspot/L4721402 42.96125, -77.43361

survey pt. (Hickory Unit, 6.11) http://ebird.org/ebird/hotspot/L3601768 42.959052, -77.429034

survey pt. (Pollinator Grassland, 2.5) http://ebird.org/ebird/hotspot/L4718764 42.96364, -77.41364

*List of eBird links:

About eBird: http://ebird.org/content/ebird/about/Entering data in eBird (website): http://help.ebird.org/customer/en/portal/articles/1972661

Entering data in eBird (Mobile App): http://help.ebird.org/customer/portal/articles/2411868

_%C2%A9DaveSpier_0393-25Fb.jpg)